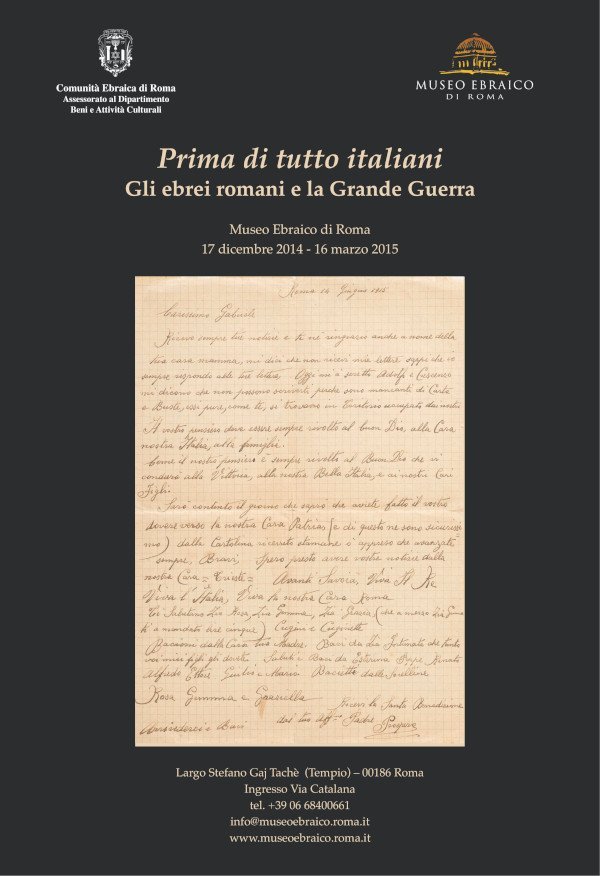

First of all Italians; Roman Jews and the Great War

(Jewish Museum of Rome, 18th December 2014 – 18th March 2015

Since the Italian Risorgimento, the Jews, hitherto considered extraneous to national values and excluded from society and military service, began to develop a strong patriotic identity, which was the same to that of the rest of the Italians. They therefore began to relegate their Judaism to the private and family dimension only.

The adhesion of Italian Jews to the First World War was therefore strong, their participation is seen as their definitive legitimization of emancipation.

The attachment of the majority of Jews to Italy and to the Savoys was strong and certain. It should therefore come as no surprise that the majority of Jews accepted Italy entering into the war with great enthusiasm.

The Italian Jews who took part in the conflict were about 5,000; 50% of them held the rank of officers (compared to 4% of the national data). The higher level of education of the majority of them (with the exception of the Romans) meant that they could hold positions of greater importance and prestige within the army. As a matter of fact, in order to take the grade of officer, it was necessary to have obtained at least a diploma of higher studies: overall, they were much more educated than the national average and their level of schooling was more advanced.

The Italian region that had the highest number of Jewish combat officers (around 500) was Piedmont, followed by Tuscany (around 400), Veneto and Emilia Romagna (around 350 each); only after these regions there was Lazio which, with Rome, could count the largest community of the peninsula.

Roman Jews were an exception to the Italian Jewish population: during the ghetto era they had dealt with commerce and continued to exercise humble trades over the centuries.

In 1870, year that marks the end of Jews segregation and the beginning of their emancipation, they were still mostly small traders, above all of fabrics, rag-sellers and craftsmen, whose level of education was rather poor. Even if their status had changed at the dawn of the Great War, the social composition remained more or less the same; so it should come as no surprise that most of those called to participate in the conflict were simple troop soldiers, with a minority of officers.

The Great War was a crucial step in the path towards the full participation of Jews in the life of Italian society. This was, indeed, the first occasion in which all male Jews faced their duty as Italian citizens, which they had become with full rights. Military courage was the most suitable response for those who identified Judaism with cowardice and hostility towards the Italian homeland.

The institution of the military Rabbinate in June 1915 was of fundamental importance: during the war, in fact, religious assistance was guaranteed to fighters of all religions. The rabbi was authorized to follow the troops to the front, in the same way as the Catholic chaplains. His authority was recognized by many as an antidote to the assimilative force of war life. He had to provide for spiritual needs by using words of consolation towards the suffering, instilling hope and giving the ones who were dying the comfort of faith.

It was therefore with the institution of the military rabbinate that all the fighters, initially reluctant to reveal and profess their identity and religion publicly, became aware and proud of being Jewish and Italian at the same time, thus sharing the same fate as their fellow citizens, who were glad to fight for their country.

Finally, it must be underlined that many of those who fought during the First World War, who were still alive in the 1930s, underwent the racial laws promulgated by fascists in Italy in 1938. Many of the 1,600 Jewish officers who lived in the 1940s perished following the persecutions during the Second World War.